Interview Archives

CorpsStories Exclusive Interviews

with Extraordinary Marines and Supporters

Winter 2002

NEW YORK – Sometimes an old Marine must make a journey of homage. And sometimes that Marine is fortunate enough to be accompanied by honoring leathernecks.

It’s sunny, brisk and cool on this November day in Jersey. But not for long. As Maj. Gene Duncan, USMC (Ret.) and the core of who becomes a consortium arrive in Manhattan, the sun slowly gives way to dark, ominous clouds.

Possibly not every Marine knows of the major. Possibly the books he’s written depicting life in the Corps from his days enlisted and commissioned, active and reserve, don’t tell it all. But many a Marine might disagree.

Duncan and former Marines Sylvester Leonard and Whitey Asheim make small talk as the hired van makes its way downtown, past Wall Street – and the line of refrigerated trucks still parked near Ground Zero.

Asheim, who spent many years in building design and construction in the city before becoming a broker with JP Morgan, reveals that evacuation drills explain the relatively low number of fatalities in the terror attacks at the World Trade Center. Every building in the city perform these drills several times a year – especially now.

Silence while passing Trinity church, where much of the management of manpower was performed during the rescue and recovery operations. It stands with beauty and grace and strength, like a spiritual fortress – amongst the commercial building and incredibly narrow streets.

Lunch

Finally the van is stopped against the curb before an Irish establishment, the Beekman Pub. Leonard and Dunk, as he’s affectionately called, pile out and begin to head across the single lane of traffic while Asheim inconspicuously covers the fare and assures the ride home later in the day.

Inside, the smells of hot food and cigarette smoke add ambiance to the already quaint atmosphere. Paneled walls and black and white mosaic tiled floors are crowded with wooden booths, barstools, chairs and starched white tablecloths. The maitre’d sets a table for 10 below the American flag. Within the quarter hour seats at the table are filled with former Marines.

John Kelly, a retired NYPD lieutenant places a stand with crossed American and Marine flags on the table. “Now it’s official,” he laughs. Kelly was a corporal in Vietnam under Dunks dearest friend, retired Capt. Tom Moore. With his wife having succumbed to cancer just the day before, Moore was on the hearts of all there.

Arriving with Kelly was another former Marine and retired NYC cop Larry Mullane. Now he does consulting for movies about these two institutions – and makes quite colorful jokes about the media.

Former leatherneck and New York City public school teacher John Garrity is a friend of Leonard and has been looking forward to meeting the author of “Green Side Out” and “Dunks Almanac.” He seats himself across from Leonard

John Scanlon, another Duncan admirer, quietly arrives. Only the Marines in the room seem to notice his bodyguard who finds a quiet booth nearby. Scanlon, former chief of patrol for the NYPD is now the Director of Homeland Security for the state of New York. He gets the coveted seat next to Dunk.

Last to arrive is another friend of Capt. Moore, Tom Nerney. The newly retired major case squad NYPD detective, Nerney is taking a breather between that and his next occupation – as consultant to Rudy Gulianni’s international consulting firm. Soon he will be off to Juarez, Mexico to find the killer or killers of nearly 300 young girls.

Most of these Marines order a lunch special after a young brunette with an off-the-boat emerald isle dialect delivers the drinks.

Dunk is inscribing books to his comrades and is trying to look casual. But the wartime method of conquering madness with humor is well in effect for these warriors who will bring him to the site of many dead – including more than a handful of their own.

Every one at this table left the Corps enlisted, except Dunk. His commissioned background is hard to disguise – even decades after fact. As they cut up and carry on, Dunk mindfully glances over his glasses at the most raucous of the moment to receive a slight slowdown in the laughs. Then he delivers sea stories so humorous that more than one leans off their seat.

Kelly motions for the waitress and soon she’s pouring a double round of Jameson Irish whiskey. He proposes a toast. All stand and suddenly the Celtic music stops and then, at full volume, the Marine hymn begins. All pop to attention and wait for the first chorus and then lift a toast. Back to attention through the second – then another down. Well orchestrated Kelly, and much appreciated on this afternoon, two days before the Corps 227th birthday.

In a somewhat foreshadowing moment, a man with arm braces to assist his crippled legs makes his way to the table. Just wanted to thank them, he said. The leathernecks all stood, humbled by this strangers report of his brother and uncle who served during different wars, and his pride in collecting mementos of their Corps duty. Another toast was raised and the realization of why they were collected – to accompany the major to a point of the fallen, was with them again.

Nerney prods them along, as it’s five minutes to staging time. Leonard and Kelly quietly cover the tab but not before the major uses his cell to have everyone sincerely offer their condolences to the captain – far away managing a wake.

Outside the pub the platoon is forming to conquer the four or so block walk to the site. Dunk, completely ignoring his lack of good health marches off at double cadence ahead of the crowd. Soon the navigators pass him, as Nerney and Mullane seek a town car at the next corner.

Nerney motions for Dunks troops to standby and reports that his friend Andr� is coming along, which brings a knowing laugh from the locals. Immediately a shiny black Lincoln turns the corner driven by a St. Croix national wearing a sport coat. Nerney opens the door for Dunk, who is appears humbled and very grateful. Leonard gets in the front for assurance purposes and Nerney slides Andr� a big bill. Soon they meet again at Ground Zero.

Private Mourning

Milling around the attractive yet very high steel fence are hundreds of quiet folks. A tall man is collecting coins while playing, “Amazing Grace” on a flute. Dunk steps from the town car. Once on the sidewalk he rocks backward, his eyes dim, and he inhales, “so this is where it happened.” He and Leonard walk to the fence and stand, silently. Although he was with the NYPD for 40 years, this is Leonard’s first visit to ground zero since it fell.

Nerney motions for the two to join the rest at a gate on the northeast corner of the site. There they meet Port Authority Police Department detective lieutenant and Joint Terrorist Task Force member, Lt. Mike Padolak. He ushers all into a van and starts his tour at the girder cross.

As the only relic remaining on display here, an undeniable presence of the good Lord washes over the mournful. Consisting of two steel I beams which fell sharply severed in the perfect proportions of a Christian cross – and wrapped on one post is a sheet metal tangle – again, just as it fell, undeniably reminiscent of a burial shroud.

Again Nerney’s invisible influence makes one realize soon that these are the only visitors inside the 16-acre land mass. No accident this gesture between he and Padolak, just honor and respect borne of years protecting each other – and burying each other’s dead. Before the tour ends it’s revealed that while Nerney spent months identifying body parts in a nearby makeshift morgue, he too has not been here since soon after the horror.

Returning to the van, the mood vacillates uncomfortably between shock and outrage to gratitude and camaraderie. Although clean of debris and even construction equipment, hollowed lower level garages and subway tunnels are constant calls from the past.

Arriving at the PAPD trailer on the south side of the site, these Marines get a greeting from one of their own, Lt. Quentin DeMarco. “You didn’t tell me we had a Marine tour!” he said smiling. The lieutenant’s somber mood broken for the moment. He too was a Marine and is clearly off-guard by the presence of Dunk. He uses windows to locate various points of reference, explains wall-size site plans and waits for the inevitable and dreaded questions. He and another PAPD officer Tony Basic, demonstrate an amazingly patient and gentlemanly attitude despite the heinous topic.

The sun is setting. A pink glimmer over the Hudson shines through the gray clouds and leaves a stunning reflection on the nearby buildings. The still vacant, and some condemned, but now washed clean, buildings.

Soon good byes are generously given to Padolak, and the van traverses a few blocks to the Met, another Irish pub inside the city municipal building compound. Another round or two, and now the old warrior needs to rest.

Leonard, his wife Patsy, Asheim and Dunk dine on steak and seafood near the Jersey hotel housing Dunk before tomorrow’s departure to the Naval Academy – another speaking engagement.

The next morning is like most for him, by 06:00 he’s fed and read and smoking and planning. More than a few fingers of a Texas fifth of Johnny Walker Red is missing, although received less than 72 hours earlier. “It spilled,” he remarks with a perfectly straight face.

He can’t really find words to express his gratitude for the events of the day before. So he goes on, writing, driving, speaking, and at every given opportunity, saying to anyone ever associated, “Thank you for your service to our Corps.” Thank you Dunk, thank you.

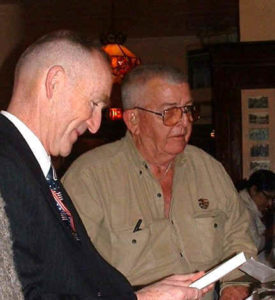

photos: Top: (l to r) PAPD officer, Sylvester Leonard, Whitey Asheim, Meriwether Ball, Tom Nerney, Maj. Duncan, John Garrity, John Kelly, Larry Mullane. Middle: John Scanlon, Maj. Duncan